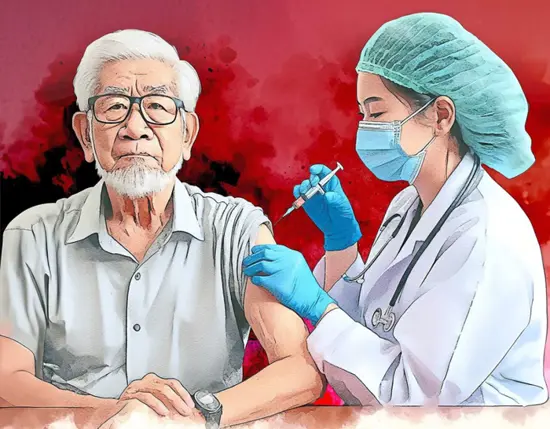

Rebooting the adult immune system when it becomes less effective

Many of us would have received a number of vaccines as a baby and child under Malaysia’s National Immunisation Programme (NIP), which started in the early 1950s.

In fact, being vaccinated throughout our first years of life has become such a norm that vaccination is usually tied to young childhood in our minds.

This idea is so prevalent that we hardly consider the need for vaccines as adults – that is, until the Covid-19 pandemic.

That period was probably the first time for many adults that the need to get vaccinated after childhood crossed their minds.

However, the ageing of our population – not just in Malaysia, but also globally – may need us to rethink this perspective.

Says GSK Global Medical Lead vice-president Dr Alexander Liakos: “It’s a fairly cruel fact of life that when we’re tiny and defenceless as children, we struggle.

“We need exposure to infectious diseases, but we also need vaccination, to keep us strong, to teach our immune systems how to grow and develop, and to stay alive.

“And we’ve done a fantastic job of that over the last 50 to 100 years.”

Speaking to international media at GSK’s vaccine manufacturing site in Wavre, Belgium, he notes that our immune systems are at their strongest in our thirties and forties.

“After that point, our immune systems start to weaken, such that we are, in the older-adult time of our lives, again susceptible to infectious diseases like pneumococcus, influenza, Covid-19, herpes zoster and others,” says the doctor.

In addition, as we age, we tend to develop chronic illnesses, like high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol and obesity, which have a negative impact on our immune system’s ability to fight off infectious diseases.

According to the 2023 National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS), over half a million adult Malaysians (2.5% of those aged 18 years and above) have four non-communicable diseases (NCDs), while almost 2.3 million have three NCDs.

Resetting the ageing system

Just like our memory and reflexes, the ageing of our immune system can not only cause it to forget how to react to certain disease-causing microorganisms (i.e. pathogens), but also cause its reactions to be suboptimal.

GSK Therapeutic Vaccine Scientific Area Immunology head Dr Yannick Vanloubbeeck explains: “At birth, the immune system of an infant is completely naive – it has never seen anything before.

“As we get older, our immune system is trained – it’s educated, like it went to school.”

This, he says, is done both through natural exposure to bacteria and viruses in our environment, as well as through vaccination.

“This exposure early in life through vaccination and throughout your young adulthood helps maintain your immune system to a certain level that is alert and can react to a vast number of pathogens.

“But when our body ages, our immune system ages as well.

“And like our brain, our memory, our immune system sometimes forgets how to react to a bacteria or a virus – even a bacteria or virus it has seen before.

“So now, you have an immune system that was trained, but it has forgot[ten its training].

“So it’s not completely naive as when we were a child, it is just a little bit suboptimal,” says the veterinarian.

He adds that aside from this “forgetfulness”, the older immune system may also react in an inappropriate manner to attacking pathogens, making the infection worse.

“And so, the vaccine we develop for older adults needs to reset the immune system to the right level.

“And resetting the immune system to a protective level requires a different vaccine composition than the one you would use in children to educate the immune system for the first time,” he explains in an interview at GSK’s vaccine research and development centre in Rixensart, Belgium.

This is where therapeutic vaccines come in.

While prophylactic vaccines protect us from the harmful effects of the pathogens they are targetted at, therapeutic vaccines are aimed at reeducating and resetting our immune system to react in the proper manner against pathogens we have already been exposed to before.

This reeducation typically involves reactivating some parts of the immune system and/or restraining other parts.

Innovative technologies

There are a number of vaccine technology platforms that are being utilised to create new vaccines, including therapeutic ones.

One such platform is the adjuvant system.

Adjuvants are substances that enhance our body’s immune response to the antigen in a vaccine.

Antigens are the key part of vaccines as these structures allow our immune system to recognise and target the pathogens they are a part of.

An example is the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which was used as the antigen in many Covid-19 vaccines.

As Dr Vanloubbeeck explains, adjuvants are like an alarm system alerting the body to the presence of the foreign antigen.

They not only help mobilise the body’s defences, but also help create a longer-lasting immune response, thus prolonging the protective period of the vaccine.

Like antigens, adjuvants are also a part of foreign microorganisms.

“Scientifically, we’ve been able to understand which molecules on the [microorganism’s] surface are actually the most efficient to stimulate our immune system.

“So we’ve identified those and we have produced them individually in a very pure form.

“And we add a little of them in the vaccine to make the adjuvant,” he says.

The trick, he notes, is balancing how much is enough to enhance the effect of the vaccine, without causing the person receiving it to become sick.

Another vaccine technology platform that is being explored is the multiple antigen presenting system (MAPS).

This platform applies to conjugate vaccines, which are used against bacteria that typically have antigens surrounded by a polysaccharide (sugar) coating.

This coating helps disguise the antigen to a certain extent, making it difficult for our immune system to recognise and target it.

Therefore, conjugate vaccines pair this polysaccharide-coated antigen with a protein antigen that is much more easily recognised by our immune system.

In addition, conjugate vaccines usually contain multiple strains of a bacteria in order to offer wider protection, with each strain represented by a particular polysaccharide-coated and protein antigen pair.

The traditional method of producing conjugate vaccines involves linking each antigen pair individually, then mixing them all up together to form the vaccine.

According to Dr Vanloubbeeck, this method is not only more laborious, but can also result in lower vaccine efficacy as our immune system is not consistently exposed to all the antigen pairs.

However, MAPS allows for the systematic bonding of the two antigens to each other, as well as between the antigen pairs, in a linear fashion.

“It is smart design – you create a chemistry that makes them click together at very specific places.

“So it simplifies your manufacturing ability – you decrease the number of steps,” he says.

In addition, he shares that data is showing this more systematic formation is also allowing the immune system to react to each antigen pair in a more equal fashion.

“It activates more broadly, the entire immune system, making the likelihood that it will fight the bacteria better,” he says.

GSK, which is a British multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company, has over 20 vaccines on the market globally and 19 more currently in development.

Its Wavre campus, which is equivalent to 70 football fields in size, is the largest vaccine manufacturing site in the world.

Leave a Reply