Essex lorry deaths: Agony builds for Vietnamese families

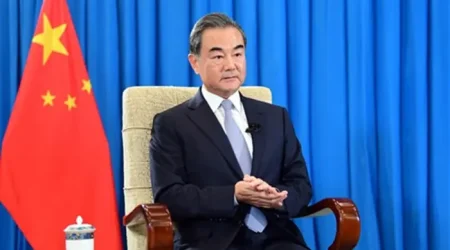

Le Minh Tuan, pictured here, fears his son, Le Van Ha, was among the dead in Essex

Le Minh Tuan, pictured here, fears his son, Le Van Ha, was among the dead in EssexInside the modest home of Le Van Ha there is wrenching despair, as his family tries to come to terms with the likelihood that he was inside the ill-fated container in Essex where 39 people were found dead.

His grandmother stares into space, covering her face with her hands. His wife Ha sits unspeaking, refusing the entreaties to eat something. His father Le Minh Tuan hugs his young grandson in desperation, and just weeps.

Le Van Ha’s story was, until the disastrous end of his journey, very typical of a young man from this poor and mainly agricultural part of Vietnam.

He followed a path trodden by thousands of others, overseas in search of better-paid work, leaving for Europe three months ago, just before the birth of his second son.

The family had borrowed to build their house, and the journey west – facilitated by human traffickers – required £20,000 ($25,000) – a huge sum for which Le Minh Tuan had to mortgage his two plots of land.

Everything hung on Le Van Ha landing a good job, and saving to pay back the loan. His world has fallen apart.

Le Minh Tuan, father of 30-year old Le Van Ha, who is feared to be among the 39 people found dead in a truck in Essex, UK

Le Minh Tuan, father of 30-year old Le Van Ha, who is feared to be among the 39 people found dead in a truck in Essex, UK“He’s left us with a huge debt,” Le Minh Tuan said. “I don’t know when we can ever pay it back. I’m an old man now, my health is poor, and I have to help bring up his children.”

Le Minh Tuan is convinced his son is dead. He received a Facebook message shortly before telling him he was about to leave for England.

It is believed most of those who died in the container came from the same district, Yen Thanh, in Nghe An province.

Neighbours are coming round to offer support, and they share in prayers before family altars, carrying photographs of the missing.

There’s a large, smiling picture of 19-year-old Bui Thi Nhung, now above the shrine in her house. Her family are praying that somehow she wasn’t in that container.

Bui Thi Nhung is from Nghe An province

Bui Thi Nhung is from Nghe An provinceHer sister Bui Thi Loan says she had a quick exchange of messages on Facebook on 21 October, when she mentioned that she was “in storage”.

“No information has been verified yet,” she says. “It’s only on the internet and social media, so we still have some hope.

Thirty nine bodies were found in the trailer container in Essex

Thirty nine bodies were found in the trailer container in Essex“We do know that there were three different lorries going to England that time, so we still hope that there is magic, and she turns out to have been on a different lorry.”

She says Nhung was the smartest of the four siblings, and had a lot of friends who helped her raise the money for the journey. Her family did not have to mortgage or sell anything.

Now they are hoping for good news, or in the worst case, for help to bring her body back to Vietnam.

The newly-built houses you see in this district are evidence of the money to be made, and saved, by working overseas. Britain appears to be the preferred destination. Some have spent time in countries like Russia or Romania, where they say it is very difficult to find well-paid jobs.

A Vietnamese woman stands near an under-construction house in Yen Thanh district

A Vietnamese woman stands near an under-construction house in Yen Thanh districtThey describe facing constant harassment in France from the police over their illegal status. But in Britain there are strong existing Vietnamese communities and jobs to be had in nail bars, restaurants or agriculture.

The brokers they deal with are part of a global network of underworld facilitators who charge huge sums for moving people illegally across borders. The amounts people pay vary, from around £10,000 to well over £30,000. The higher sum is supposed to be for a “VIP service”.

Many of them go out of Vietnam via China. But when they reach the English Channel the only reliable way across is by being smuggled inside containers, regardless of what fee is paid.

In the aftermath of the tragedy in Essex, the Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc has ordered an investigation into trafficking networks. But trafficking has long been a serious problem, often involving women and children. This year the country was downgraded in the annual US State Department’s Trafficking in Persons report.

Whatever measures the government is taking, the huge sums of money made from trafficking make it a lucrative and tenacious business that still thrives in Vietnam.

Source: BCC

Leave a Reply