Chinese crackdown on online fraud forces citizens to leave Myanmar’s ‘Little China’

At a hotel in Wa State, near the Myanmar-China border, Chinese national Li Jiajie is growing increasingly desperate by the day.

The 24-year-old has been surviving on his savings since last month when he quit his job as an assistant chef after Chinese security officials instructed all citizens to leave northeast Myanmar .

But Li is uncertain how long he might have to wait before he can enter quarantine in Pangkham, the main city in the state, before crossing the border to reach his homeland.

“Only a few hundred people a day are allowed to enter the quarantine centre in Pangkham,” he said. “There are at least tens of thousands of people in the queue. I have quit my job and desperately want to go back, but I may have to wait here for months.”

Li is among an estimated tens of thousands of Chinese nationals who have been caught up in the sweeping crackdown by local authorities in China on telecoms and internet fraud in areas on the Myanmar side of the border, where gangs that run illegal casinos and scams are known to be based.

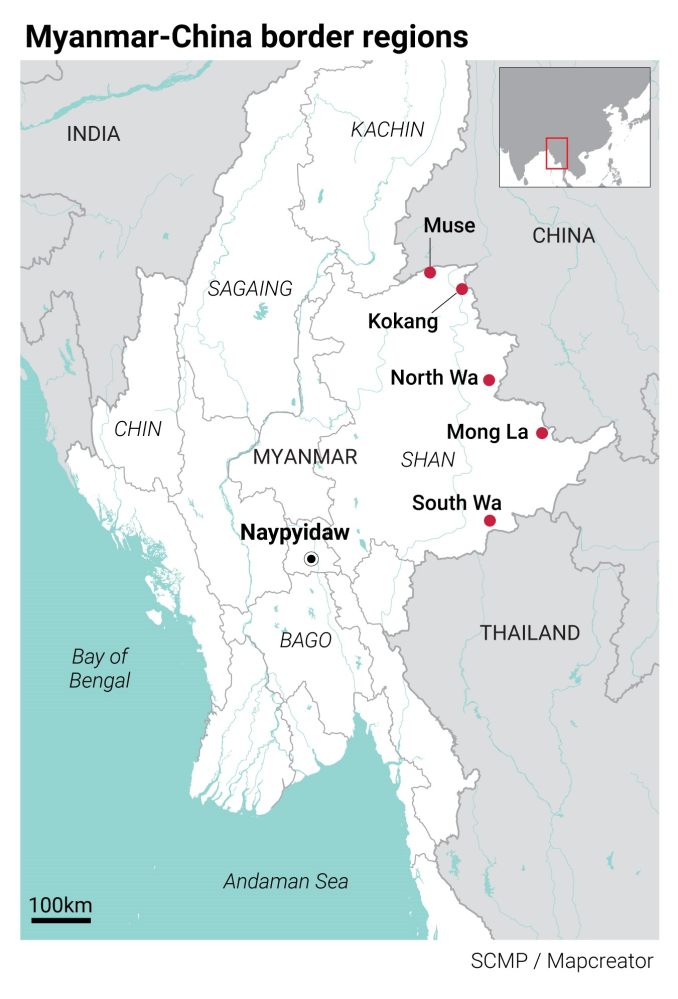

Local public security bureaus across China in May initially told suspects who were connected to internet fraud in Myanmar’s border regions – specifically the Muse, Kokang, Wa State and Mong La areas – to return home, but the scope of the recall was soon expanded with new directives and notices emerging on social media by June calling “all nationals in northern Myanmar” to return.

Security officials said anyone who refused to comply would find themselves and their family members restricted from accessing welfare, subsidies and public services in China.

The move has affected people such as Li, who deny taking part in illegal activities in northern Wa State and insist they are simply trying to make a living.

Li, who sneaked across the border from a second-tier city in eastern China about a year ago, said he decided to pack up because “if most of the Chinese people go back, we would not be able to do business well here”.

Chinese in Wa State

Wa State is a de facto independent region, with its own political and administrative system, that has been more or less left to its own devices by Naypyidaw. Mandarin is the lingua franca of the state and people use telecoms networks and financial services from China.

The state has a total area of 35,000 sq km, roughly the size of the Netherlands, across its two separated regions that are home to some 700,000 people. In the north, the Chinese yuan is used, while the southern area that borders Thailand uses the baht.

Some 100,000 people in Wa State are Chinese nationals, most of them migrant workers or small business owners in the north, and they make significant contributions to the economy. The territory is dubbed “Little China” or “Shanzhai China”.

At the restaurant where Li worked, the bulk of patrons worked in the online gambling industry in Moung Neng, a county near Pangkham. He said he found the lavish lifestyle there “astounding but eye-opening”.

“The capital of Wa State just looks like a small town in China, but the price levels are virtually as high as those in China’s first-tier cities, like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou,” Li said.

“The local people are not rich, and many of them work for Chinese nationals. The prices of goods and services were pushed up by the Chinese who came here. “Chinese customers here are willing to spend large sums of money. They don’t have a problem spending 2,000 to 3,000 yuan on two or three people’s meals.”

Business remained bullish until Covid-19 began to spread wide in Wa State late last year, triggering restrictions on movement.

Drastic threats

According to a widely circulated but unverified leaked spreadsheet compiled by Chinese public security authorities, more than 141,000 Chinese nationals have been listed as individuals who should be “persuaded to return”.

They mainly hailed from impoverished or less-developed cities in Fujian, Hunan, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces.

“I can guarantee with my life and reputation that over 90 per cent of people on the list are just ordinary civilians who do business honestly,” said a Chinese businessman who actively helps compatriots return home, and asked not to be named.

“They lead a tough life abroad and have invested all their savings,” he said.

The approach by provinces to recall their citizens varied according to locality, said several Chinese sources with links to Wa State.

Some Chinese officials have allowed the citizens who managed to provide proof of lawful business to stay in northeast Myanmar, or promised to exempt them from criminal prosecution. Others insisted that their citizens return by the June 30 deadline, regardless of whatever documents they can provide or their ability to gain a quarantine spot.

The businessman who assists his compatriots claimed some regions had taken drastic measures to force people to leave the Southeast Asian country.

“Some provinces demolished those people’s homes, painted ‘home of frauds’ on their houses, or threatened to stop their children from going to school,” he said. “This is just too much.”

The four provinces listed in the spreadsheet as the main sources of the workers were behind the most forceful methods of inducement, he claimed.

The journey home

Under current regulations, Chinese citizens must quarantine for five days in Pangkham and three weeks in Menglian county in neighbouring Yunnan province before being allowed to return to their hometowns.

Quarantine in Pangkham costs between 1,200 and 1,600 yuan (US$186 to US$248), and Chinese nationals must also take seven Covid-19 tests in Menglian, according to a businessman who wanted to be known as Haishi.

“Women can stay at a hotel, while men can only stay at corrugated iron houses,” said 45-year-old Haishi, who is currently in isolation in Menglian county. “It is very hot here in the corrugated iron houses. The internet connection is extremely unstable.”

A native of a third-tier Fujian city, Haishi mortgaged his house to set up a supermarket and a food shop in Mong Pauk, south of Pangkham, in June 2019.

When the pandemic broke out, he was in China, and he agonised for six months over whether to return to Wa State through unofficial channels to save his business.

After the recall policy was announced, Haishi submitted copies of his Wa State business registration and taxation certificates to officials in his hometown in May. But the next month, authorities began harassing his parents, who are in their 70s, and threatened to cancel his household registration, or hukou, and bank accounts, he claimed. Even his children’s education was at risk.

“I was helpless,” Haishi said. “My situation is very ubiquitous – owing a lot of debts, [having to take care of] the elderly and children, having properties trapped here, and not knowing when I can come back again.”

During his scramble to leave Myanmar, he was forced to sell his car for a third its original price, while he could not find anyone to take over his shops or buy his stock of goods.

Haishi said he heard some people had sold their properties at one-tenth of the market price.

Is it legal?

The extreme measures taken as part of the crackdown have raised questions on whether they are in line with Chinese law.

“[The Chinese public security authorities] are treating the over 100,000 nationals in northern Myanmar as criminals. This is a presumption of guilt,” said a Chinese businessman in Pangkham who exited China and entered Myanmar legally last year, but was still named on the spreadsheet.

“China now is such a thriving and prosperous country, it is hard to believe that the authorities do such things,” said the businessman, who declined to be named. “This is bitterly disappointing.”

Teng Biao, Pozen Visiting Professor at the University of Chicago and a former human rights lawyer in China, said the punishments laid out by officials transgressed Chinese and modern legal principles, but were not new in practice.

“The principle of bearing responsibility solely for one’s own crime is that the punishment only applies to the offender himself,” he said.

Teng cited Article 59 of the Chinese Criminal Law, which states that “confiscation of property is the confiscation of a part or all of a criminal’s personally owned property, and property belonging to the criminal’s family members shall not be confiscated”.

“Although the provision of the Criminal Law is somewhat narrow, the principle is widely recognised in the academic and judicial theories,” he said.

A human rights law professor at a Chinese university who requested anonymity due to sensitivity of the issue, said that in China, a gulf existed between political vetting for public offices and party membership and the legal requirement for ordinary citizens. The first can “indeed be stricter than the conditions set by law” and it is justifiable for the authorities to be “extra stringent” when vetting family members of those who fail to come back in time, the professor said.

Pushed out

Since the recall notice, many of the major cities in Wa State have become rather bleak, with many shops and buildings emptied or abandoned, according to local sources. The same scenario is playing out in other areas near the China border, including Mong La and parts of Laukkaing, the capital of Kokang.

Authorities in Wa State and Mong La, another self-administered region that relies heavily on China for trade, have taken heed of the consequences of the Chinese local authorities’ push to drive its nationals home.

But the effect of the policy is less conspicuous in Kokang, which is ruled by local elites who have a strong relationship with Myanmar’s military, also known as the Tatmadaw. Muse, a major border trade town controlled by the Tatmadaw, has also not seen a large number of shops abandoned.

Wa State is a one-party de facto state ruled by the United Wa State Party, which controls the most powerful ethnic armed group in Myanmar – the United Wa State Army.

In a shift away from its leadership’s previous ostensible “non-intervention” posture towards the black market economy, Bao Youxiang – the supreme leader of Wa State – wrote in a letter dated June 17 that China’s move to combat telecoms frauds by recalling its nationals in northeast Myanmar had significantly affected normal businesses.

“All the supplies and technologies we need depend on China,” the 71-year-old Bao said in the letter. “To survive and develop, we cannot go against China’s policy. Therefore, I have decided to entirely ban the online gambling industry within the state.”

On June 20, the party announced it would investigate people and companies involved in telecoms fraud and online gambling, while simultaneously working with Chinese authorities to repatriate suspects.

Likewise, the Mong La government issued a letter on the same day, saying that given the recall order, local authorities would provide assistance to those who wanted to return to China.

“We will do our best to negotiate with the relevant departments of the Chinese side to create a better environment for your investment in our area,” it said. “[We] will continue to actively respond to China’s Belt and Road Initiative .”

According to Jason Tower, country director for the Myanmar programme at the United States Institute of Peace, an American federal institution tasked with promoting conflict resolution and prevention worldwide, China’s cross-border online gambling industry could be divided into at least three tiers.

At the top of the hierarchy are the players who control the large operating concessions, have strong ties with local elites, militia leaders or other corrupt actors that provide cover and protection for the illicit activity, and often have managed to obtain citizenship in the host country, he said.

The second tier consists of subcontractors that operate individual online casino or fraud operations from within the zones. Unlike kingpins, they do not necessarily have the political connections or influence needed to buy citizenship or secure protection from a host country, and as a result they are at higher risk of being targeted by the Chinese authorities, Tower added.

The third tier are those most likely to be arrested – those who get hired by the subcontractors in the zones to work in call centres that the Chinese public security authorities claim are being used to carry out fraud or lure unsuspecting Chinese into playing online casino games, Tower said.

“[The third tier] represent the ‘foot soldiers’ of the industry – and they are the primary target of China’s current crackdown,” he said.

“The questions to raise are – why are many of the kingpins remaining at large, why do host governments tolerate this and why does Chinese policy not directly target the criminal actors that back zones like Saixigang in Myanmar or the countless resorts built to host criminal activity in Sihanoukville?”

A senior financial professional at one of the five conglomerates in Kokang, who identified himself as “Zhang San”, said: “The major conglomerates which are also involved in the online gambling industry have not been enthusiastic about cooperating with China. Many Chinese workers left, but the core members of the shadow industry remain here.”

Meanwhile, as Li counts the days in his hotel in Pangkham, he says the online gambling industry is now facing a dearth of workers.

“The policy has appeared effective in Wa State. The online gambling companies are desperate for employees. They used to recruit only Chinese nationals, but they are open to locals now.

“The rate for a traded worker has increased to 30,000 (S$6,200)or 40,000 yuan,” Li said, referring to the payments companies make to trade workers whose movements are controlled over debts or other reasons. “It used to be just several thousand yuan.”

Comment (1)

I’m not sure where you are getting your info, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more.

Thanks for great information I was looking for

this info for my mission.