In unaffordable Seoul, housing is at the centre of the South Korea election

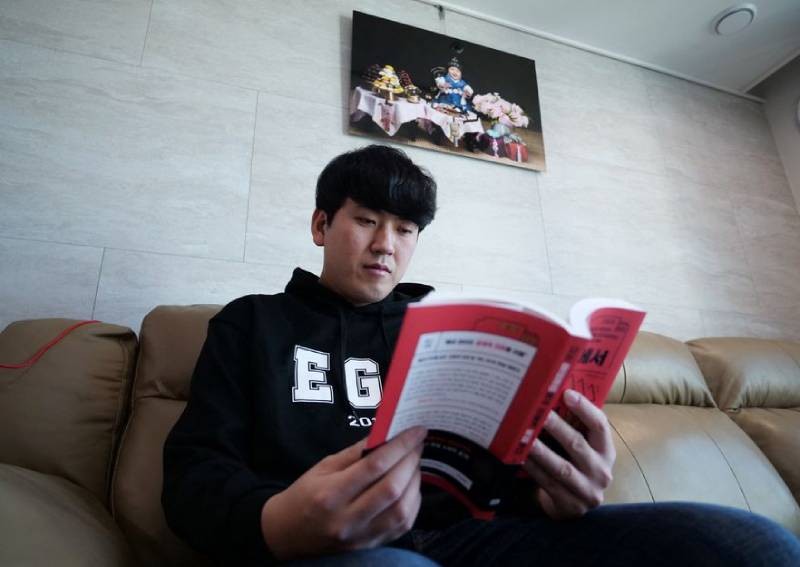

Lee Jae-hong would have had no trouble buying a home in the suburb of Ilsan on the outskirts of Seoul back in 2018. With a strong credit score and a job at a blue chip company, borrowing enough for an average apartment in the city costing about US$562,000 (S$763,000) was well within reach.

But the now 39-year-old held off thinking there would be better opportunities in the coming years — only to be “gobsmacked” by a near tripling of prices in his neighbourhood since President Moon Jae-in took office in 2017.

Housing has emerged as a critical issue in the presidential election slated for March 9, as Lee and millions of others who missed getting onto the property ladder blame the government for failing in its promises to make housing more affordable.

“I would do anything, if I can go back in time, to buy something,” said Lee, who has delayed his marriage and retirement plans due to his financial uncertainty.

“Those who think they can control the (property) market should never be in power again.”

Now a YouTuber, Lee said he will vote for Yoon Suk-yeol from the opposition party, whose policy pledges including cutting capital gains taxes and deregulating rules on knock down-and-rebuild homes are regarded more market friendly than those of Lee Jae-myung from Moon’s progressive camp.

Lee’s decision not to buy a property left him far worse off than peers like Park Seong-eun.

Park ignored Moon’s policy visions and in 2017 bought two apartments in Gwangmyeong, west of Seoul, when local rules allowed him to borrow as much as 70 per cent of a property’s value.

An on-paper gain of around 1.2 billion won (US$1 million) on his investments mean his retail management job is now a choice not a necessity, said Park, who is also 39.

“When I have a bad day at work I think about retiring early and having a simple life. I can do that because prices doubled to over 1.1 billion won, both of them,” said Park.

He plans to vote for someone who would ease investment rules again so that he can buy one more property.

Curbs fail

Moon promised to make South Korea more equitable by curbing what he believed was the root causes of the country’s economic inequality, real estate speculation.

He raised capital gains taxes on multiple homes and repeatedly tightened loan restrictions, especially for higher priced apartments. Starting with Seoul, the government designated more and more parts of surrounding satellite cities as speculative zones subject to tightened mortgage rules and raised tax rates on ownership of pricey properties.

But his five-year term has been marked by endless debates about his policies, which critics say inflicted pain on those he intended to help and benefited those who did the opposite of what the government advised – snap up homes using debt.

Moon’s approval rating slid to 43per cent from as high as 84per cent when he took office in 2017, the latest poll by Gallup Korea showed. Those who disapprove of his performance cite his failure to tamp down real estate speculation as the biggest disappointment.

The average price of an apartment in Seoul more than doubled in the past five years to 1.26 billion won in January, making it less affordable than cities like New York, Tokyo and Singapore, relative to income.

Curbing real estate speculating is only one of many challenges the next leader will need to address, which includes sustaining growth at rates matching the economic potential after an estimated 4per cent expansion last year, the fastest since 2010.

Still, Moon’s pledges to fix some major economic problems remain unfulfilled.

The economy ended up creating an average of about 172,700 jobs per year between 2017 and 2021, fewer than half of what he had promised, after a combined 41.6per cent hike in minimum wages and a reduction in working hours.

For those who got on the property ladder, the future looks far brighter.

Jang Sung-won, 32, left his civil servant job in November to run a YouTube channel and write books as his 2019 purchase of a three-bedroom home gave him confidence that growing equity could be enough to support his pregnant wife and a child.

“I don’t think I could have made long-term plans, with our second child coming, without securing this home. That’s difficult if we are hopping from one studio or a small flat to another, right?”

“I’m just really grateful, but at the same time I feel bad for others my age. They will now need much more seed money to buy home.”

Leave a Reply